I think it’s time to talk about a recipe that I periodically use in place of my water-only rinses for my scalp and hair.

In some of my previous posts I’ve talked a little bit about the Kaolin clay, rice flour, and corn starch powder mixes that I use almost daily for conditioning my scalp; not for hydration, but rather as a natural, gentle method of managing scalp oil and exfoliating dead cells around the hair follicles. I like to apply these powder mixes to my scalp and roots, massage, let them sit for several minutes, and then comb and brush it all out. If there’s any oil left from the first comb-through, I go back and apply a light amount of the powder to the trouble spots and repeat the process until the oil is down to a low level. The goal is not to remove all the oils, but rather to clean and prep the scalp for new hair growth as this allows my scalp to be calm and nourish its own hair.

About once a week or so, sometimes every two, I will do a water-only rinse where I thoroughly massage my scalp while letting warm (but not hot!) water run over my scalp and through my roots. This helps ensure I get any leftover powder out of my scalp and out of any follicles that my boar’s hair bristle brushes and sandalwood combs may have missed. Again, I don’t use shampoo and I don’t wash my hair during the rinse because my goal is to leave just a little natural oil production so my scalp doesn’t dry out and start overproducing oils.

It’s sometimes during one of these rinses that I’ve actually not used water from the tap but instead from a rice-water recipe inspired by the Red Yao Women of China. I’m pretty sure most of you have heard about this already, but for those unfamiliar with it, Isabella Demarko put together a nice video on the subject here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K9Ie7aeyYqg. Mercy Gono BSN, RN has also made a video of her own (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_VUd4UhdS8), explaining the tweaks she made for applying to her lovely natural textured hair. Both women use a near identical recipe as each other’s and both took notes from interviews of the Yao.

I had actually held off talking about this since January of this year because I was originally skeptical whether this recipe would work as intended when pulled out of its original context and culture. I say this not to imply the recipe is ineffective or a waste of time (it’s effective), but because you have to understand the culture being interviewed and the culture conducting the interviews and who is later disseminating it across the web. This context has a lot of implications for how you should use it and, more importantly, whether it will work for you–it depends on what other things you maybe are or aren’t doing to your hair.

From our modern, Western perspective, we are on the hunt for that one trick, that one magic bullet that will cure our hair woes and let us achieve the hair we’ve always wanted. Unfortunately, this then leads to misconceptions about the potency of the rice-water recipe. This is coming out of a culture that thinks it needs to wash the head with soap literally every day or every other day, uses heat styling, and that heavily relies on commercial and drugstore products which were never intended for people with long hair.

The sad reality is that all these modern products are designed with the assumption that you aren’t going to grow your hair longer than maybe your shoulders, and they are advertised to imply that your body is broken or defective without their products, making you think you need to rely on them for better results. So many women in the West also don’t apply soaps to their roots, but rather swirl it around in their hair, meaning their scalp doesn’t get clean and their hair gets incredibly dry and brittle. Hair is also seen as a fashion accessory, intended to be worn down and lose, regularly styled, and ultimately left exposed to sun damage, friction, and tangling. We as a culture have forgotten the basic essentials for caring for our hair and it’s no wonder everyone latches on to a “secret” or “special” recipe from far away to fix our problems.

From the Yao women’s perspective, their culture values regular use of some seriously protective hair styles, and you may notice that all the tourists have to wait until the women rinse their hair to see just how long it is because it is otherwise kept neatly wrapped atop their heads. They also don’t use all the soaps and sprays, serums, conditioners, and masks that are widely marketed in the US, but instead rely on gentler methods–regular rinses instead of washes. They never cut or style their hair, never let it hang loose, and don’t touch it much once it’s set in place. So when foreigners come knocking at their door holding cameras and asking what these women attribute their long hair to, they don’t go to explain their whole culture and mindset because they feel it is common sense. Instead they point to something within that world, their rice-water, that they find is a helpful addition to their regular regimen.

So why did I title my post the way I did? Partly because it is true, but also because I recognize that so many women are thinking through the modern, Western perspective and I’d hope that by making a title that fits this lens, they just might find not only the Yao recipe but the Yao mindset. Women in the Victorian era understood this same mindset and as a result, got some of the most gorgeous Rapunzel hair ever seen in photos that still leads people to “ooh” and “ahh” to this day. Katherine Haircare goes extensively into the Victorian side of things and I highly recommend her blog if you haven’t seen it already.

Now that’ we’ve established the context in which the rice-water rinse originally exists, let’s talk about the recipe itself, how I’ve tweaked it for my needs, and how I use it in my own life.

Natalie’s Rice-Water Hair Rinse:

- Rice, approx. 1-2 cups

- Water, filtered

- Citrus fruit rind, peeled or granulated (1 tbs)

- Maca root, slices or powder (1 tsp)

- Ginger root, slices or powder (1 tsp)

- Amla fruit, powder (1 tsp)

- Spice cloves, whole (1 tsp)

- Bowl

- Stock pot

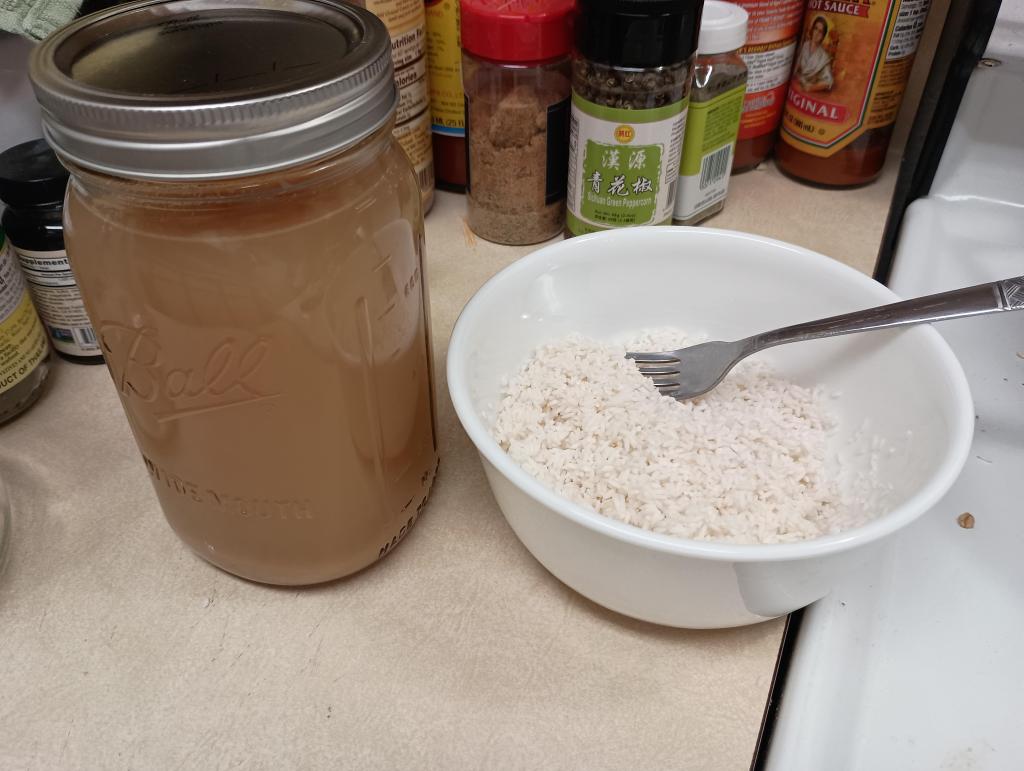

- Mason or Ball jar

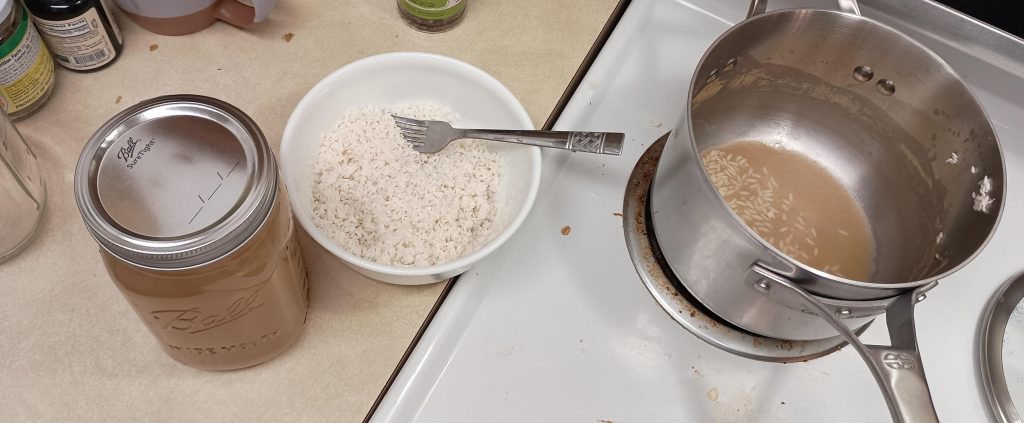

Take the dry, uncooked rice and pour it into a bowl. Fill with filtered water just to cover. Then take the grains in your fingertips and rub them together, mixing the rice around until the water turns cloudy and white. If your rice is pre-washed, you can keep this water (no need to discard this like the Yao do, as they are taking freshly harvested grains that may be dusty). Pour this water off the rice and into the stock pot, taking care to not let rice fall into the pot. If it does, just scoop it back out. You can see I made this mistake in the above picture 😉

Fill the bowl again and rub and mix the rice around until the water again turns cloudy white. Some people do this for about five minutes and then just set the rice aside. I like to continue repeating this process about three or four times, five minutes each, to really get all I can out of the rice. The stock pot should have a good amount of water in the bottom. At this point I often note the skin on my fingers feels nice and soft from having been exposed to the starch in the rice-water. This is exactly what we want because our hair benefits from this, too.

Turn on the heat to a level that, for your stove and particular burner, will let the water reach a low boil. As it reaches up to temperature, this is the time to add those extra ingredients to make it smell nice and add some extra benefits to the rinse. A lot of people add citrus rind (pomelo or orange). As I don’t keep citrus around, I decided I’d like to see what it would act like if I didn’t add any citrus. Maybe this will lessen the effects, maybe not. Time will tell. If you want to be as authentic as possible, you can add the peel to your pot. I intend to add some to mine going forward.

Next I like to add the ginger and maca roots, amla fruit, and cloves as they imbue the water with properties that I see in time-honored ayurvedic tradition. The goal with these secret ingredients is to chose something you enjoy the smell of but also provides nourishing and anti-inflammatory properties. My first time making this recipe I only added ginger and maca, but going forward I’ve tried other ingredients. It makes me wonder if using garlic would also be healthy for my scalp. I know the smell isn’t exactly pretty but, if it does the trick, I always have a lot on hand that I could use, especially as this is just a rinse and not a leave-in treatment.

Boil the rice-water and added ingredients for about 10 minutes and then pull off the heat. Pour this into a Mason or Ball jar that you know is rated for hot temperatures (no one wants fractured glass and hot water everywhere!) and let it cool. This jar is then stored in a dark and cool place. I like to let it sit for two weeks or longer as the Yao women let theirs sit for a month. I can wait this long as I only rinse my head about once a week and only then use the rice-water rinse every other. If this is too long for you, many women I’ve seen online here in the US, Canada, and Europe elect to let theirs go only for a week, so maybe that is still effective. The starch and nutrients will condition your hair and scalp either way, but I think the fermentation for two+ weeks works to bring out those properties even more.

When your jar has sat for long enough, chose a pouring or spraying method that works best for your hair type and do it over a bowl so you can catch the water that runs off. I like to re-use the water that falls a few times before discarding it so that I get the most out of the rinse. Let this sit in your hair for about half an hour and then use normal water to rinse the rest out of your hair. Congrats, you’ve just used a really nifty haircare technique! 🙂

If you use this alongside clay washes or hair-powders, and in lieu of modern shampoos, you should get some excellent results with scalp health and hair growth. If you want to know more about these other methods, feel free to check out the rest of my blog. Thanks for joining me!

Leave a comment